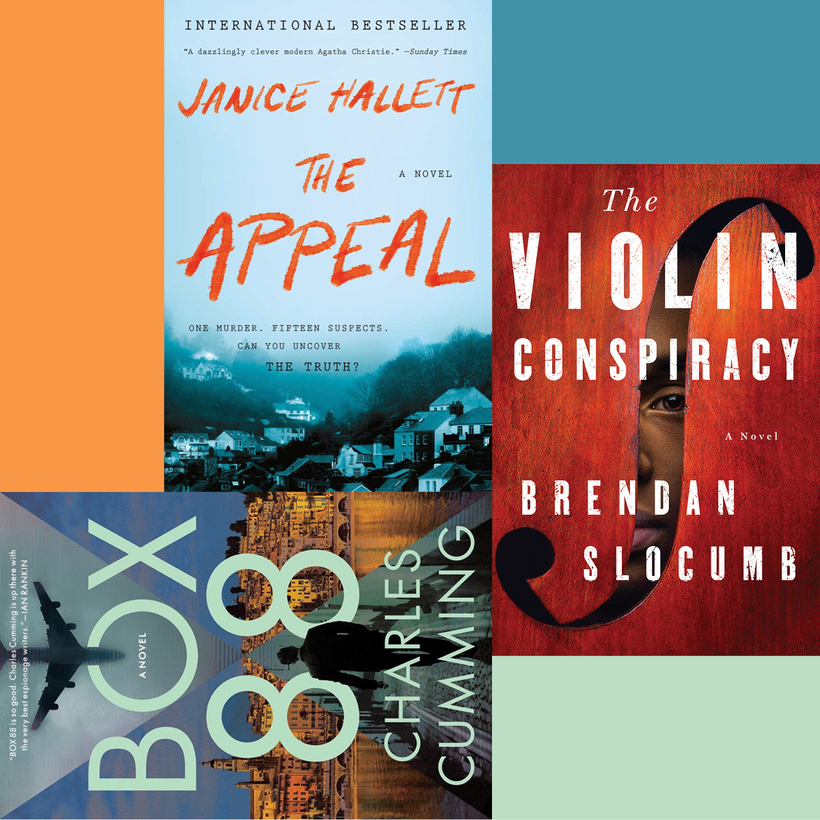

Anyone who has participated in a school benefit auction will recognize the adrenalized altruism practiced by the good people of an English community in The Appeal. To fill the coffers of a crowd-funding campaign for a sick child, they come up with yogathons, bake-offs, dinner dances, merchandise, distance swims—even an “Elvis cookathon,” whatever that is. Because why should money be the difference between life and death for two-year-old Poppy, who has been diagnosed with a rare form of brain cancer, potentially curable by an experimental—and expensive—drug therapy available in the U.S.?

This is the question posed by Martin Hayward, the child’s grandfather, in an e-mail blast, and thus is born “A Cure for Poppy.” Hayward is the patriarch of the town’s alpha family, and at the same time everyone is working furiously to save Poppy, the Haywards’ community-theater group is getting ready to present Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, doubling down on the drama.